Citizen Kane, you say? Birth of a Nation, perhaps? Ghidrah the Three-Headed Monster?

No, no, and no. (Well, we'll give you a "maybe" on that last one).

If by "influential," you mean a film with the power to alter the course of human events, then add John Huston's We Were Strangers to your short list.

Never heard of it? No wonder. It's one of Hollywood's best kept secrets, and has been since it was yanked from theaters following its brief run in 1949. Finally, in 2000 it was released by on DVD by Columbia Pictures.

The undeniable fact is this: We Were Strangers is the film Lee Harvey Oswald watched less than six weeks before allegedly gunning down President John F. Kennedy on the streets of Dallas. In fact, Oswald viewed this movie twice, and with great interest, at the Irving, Texas home of Ruth Paine (where Lee's wife Marina was staying).

Oswald watched We Were Strangers on the evening of Saturday, October12, 1963, and again in the afternoon of Sunday, October 13. We know this because Marina mentioned it in her 1964 testimony to the government's official investigating body, the Warren Commission.

Just when you thought every last drop of ink had been spilled over the JFK assassination, along comes researcher/writerJohn Loken, who has spent the last few years trumpeting a pet theory of his own: The "trigger effect" that We Were Strangers had on Lee Oswald. (See the following John Loken interview).

Loken is no Aliens-Did-It nut job; he's strictly an Oswald-as-lone-gunman guy. Loken's recent book, Oswald's Trigger Films, provides a sober case for the motivating effect We Were Strangers must have had on the impressionable, 23-year-old Oswald. Loken's theory is intriguing enough to merit a reconsideration of Huston's forgotten We Were Strangers.

Herewith, a brief plot synopsis of the film, which was based on an actual incident that occured in Cuba in 1933:

American leftist (John Garfield as Tony Fenner) returns to his native Cuba to overthrow dictatorial Cuban president Gerardo Machado. Fenner cobbles together a band of conspirators including, naturally, a beautiful brunette (Jennifer Jones as China Valdez) and a guitar-strumming proletariet (Gilbert Roland as Guiliermo). While avoiding the prying eyes of the chief of Secret Police (Pedro Armendiaz as Aliete), the plotters attempt to plant an underground bomb beneath Machado and his cabinet. The plan comes to a dismal end and Fenner is killed. Even as Fenner lays dying, however, Havana streets fill with sounds of jubilation. The people's movement is at that very moment sweeping the Machado regime from power.

Viewed today, We Were Strangers explodes with scenes and dialogue that would have resonated deeply within Lee Oswald's tortured psyche. Imagine, if you will, Oswald--president and sole member of the New Orleans chapter of the Fair Play For Cuba Committee--lying on the couch at 2515 W. 5th Street in Irving, his head on Marina's lap, as the following unfolds on screen:

>>A freedom-fighter is arrested for distributing FREE CUBA leaflets on Havana's streets. (Oswald had been arrested in August 1963, on the streets of New Orleans, after distributing Fair Play for Cuba leaflets).

>>A politician is assassinated while riding in an open automobile.

>>Co-conspirator Guiliermo says: "A man with a shovel leads two lives, his mind seldom on his work, spending most of his time dreaming." (Oswald has spent the 18 months at a series of menial jobs, all the while plotting to kill--first, right-wing General Edwin Walker, then JFK. Guiliermo's description fits Oswald to the marrow).

>>China Valdez' brother Manolo, voice dripping with disdain: "I've heard all the excuses" (not to join the people's movement). 'I'd join you but I have a wife and family...' " (Oswald himself is at just such a critical juncture. Kennedy is coming to Dallas, presenting Lee with his singular shot at infamy--and, like Fenner, matrydom. But alas, Oswald and wife Marina are expecting their second child soon).

>>Protagonist Fenner, an American citizen heroically committed to Cuban liberation, unflinchingly embraces violence as a morally-justifiable means of political change.

>>The film's very theme: That martyrdom to a fervent cause is ultimately its own reward. In the words of Tony Fenner: "The tomb is not the end. It is merely the way."

BIRTH OF A MOVIE

The origins of the film We Were Strangers can be traced to a 1948 Hollywood party. Director John Huston, fresh off Key Largo, was approached mid-cocktail by independent producer Sam Spiegel with the suggestion they create their own film company. "Come up with the money," Huston remembers telling Speigel in his 1980 bio Open Book, "and you've got yourself a partner."

Thus Horizon Pictures was born, but not without complications. "Sam and I were eager to get the company going," Huston recalled, "so hurriedly, prematurely, we decided upon We Were Strangers as our first picture." Spiegel scheduled a meeting with MGM studio boss L.B. Mayer to discuss financing.The night before the meeting, Huston attended a party at Humphrey Bogart's, an all-nighter in which Bogie's living room furniture was removed to accommodate an indoor football game. "I got as drunk as I've ever been in my life," Huston said.

The next morning Huston was awakened by a phone call from Spiegel. "For Chrissake get over here immediately. We've got to make that meeting!" Bogie's valet drove Huston to Spiegel's, where he borrowed pants and shirt from the diminutive producer. With "cuffs up o my elbows," Huston, along with Spiegel, arrived at MGM."I was nursing a hangover only a bullet could cure," Huston recalled.

So the task fell to Spiegel, who pitched the film with animated fervor, making up scenes as he went along. Days later, the two were informed that Mayer had expressed reservations about dealing with the oft-difficult Spiegel. As it turned out, Spiegel had already cut a deal with Columbia Pictures. The project was on.

Frequent Huston-collaborator Peter Viertel wrote the screenplay based on an incident from Robert Sylvester's book Rough Sketch. Viertel's characters spit out spare, rhythmic dialogue, reflecting the director's fascination with the prose of Ernest Hemingway--a drinking companion, by the way, to both Huston and Viertel.

Huston's first choice for the female lead was a virtually unknown 22-year-old starlet named Marilyn Monroe. When Spiegel balked at spending the money to screen test Monroe, the part went to Jennifer Jones, who'd received an Oscar in 1943 for Song of Bernadette. So thoroughly does Jones embody China Valdez--part siren, all radicalized fem fatale--that it's impossible to imagine the breathless uberblonde in the role. (Monroe would make her screen debut in Huston's next film, 1950's Asphalt Jungle).

In retrospect, casting John Garfield as Tony Fenner injects the film with an eerie backstory, as Garfield would soon find his career in shards compliments of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Pedro Armendiaz turns in a near film-stealing performance as the head of Cuba's oppressive Secret Police. (Armendiaz would commit suicide in 1963 after learning he had contracted cancer on the set of the 1953 flick The Conquerors, filmed on the Utah flats adjacent to a govenment nuclear test site. Fellow cast members John Wayne, Dick Powell, Anges Morehead, and Susan Haward all would die of cancer. But that's fodder for another article).

The film was shot on location in Havana, where quaint cobblestone streets and tropical courtyards provided a layer of authenticity. Scenes play out in dark, brooding, noir-like sequences, compliments of cinematographer Russell Metty (Spartacus, 1960; The Misfits, 1961).

The project was given the working title We Were Strangers--which, one sanguine critic suggested, could have been the working title for any John Huston picture. In a rare Hitchcockian cameo, Huston briefly appears in an early scene as a Cuban bank teller.

We Were Strangers, released in April of 1949, managed to anger both right- and left-wingers, and proved a financial disaster for Horizon. Bosley Crowther of the New York Times described it as "a morbid melodrama...written poorly and clumsily played" with a "plot that goes sour." Its not surprising that We Were Strangers died at the box office. It was, after all, a movie in which ideas, and radical ideas at that, substituted for action--sure-fire box office poison.

It was quietly yanked from theaters following a brief run, and from 1949 to 1963 it remained Huston's least-remembered film--even by the director himself. When asked about We Were Strangers in 1972 by a reporter for Sight and Sound Magazine, Huston admitted: "I don't think I've seen it since I made it."

A REBIRTH

Today, five years after its release on DVD, We Were Strangers seems to be enjoying a rebirth of interest. A recent perusal of internet movie review sites yields a wealth of opinion--mostly favorable. To wit:

>> "The overlooked We Were Strangers is one of the best of (Huston's) more obscure titles...As good as film as Hollywood could make about Latin American reality in 1949 (when) America wasn't ready for the disturbing notion of heroes that hide from the law while plotting abominable crimes...Ends in an existential gun battle that plays as a precursor to bloody last stands in later violent epics like The Wild Bunch..." --DVDTalk

>> "Moody, atmospheric, bordering on surreal...intended by Huston as an allegory for the repressive American government during the Red Scare. Although this point was ultimately missed by audiences of all political persuasions, the film nonetheless remains a masterpiece of the suspense genre..." --Yahoo!Movies

>> "An astounding anomaly in Hollywood film-making, in that it is openly supportive of armed revolutionary terrorism, even if it means the death of innocent people. A first-rate, taut, well-constructed thriller with convincing characterizations and strong direction..."

--IMBd

>> "One of the first films of the post-World War II period to attempt to encapsulate the new geopolitical landscape into a compelling dramatic narrative...some fourteen years before "The Manchurian Candidate," Huston's film tackled similarly explosive issues. Strangely prescient with respect to the later Cuban revolution and the ascendance of Fidel Castro." --BoxOffice

It is revealing that even today's revisionist critics miss the film's intimate connection to the Kennedy assassination. Yet it is undeniable that Lee Oswald watched this movie twice in two days in mid-October 1963. The question persists: Does that fact make Were Were Strangers a film of incalculable historical impact, or merely an item of morbid curiosity?

Answers in the Kennedy case have never come easy, if at all. Still, the possibility exists that co-conspirators were indeed lurking in Dallas on November 22, 1963. Not flesh-and-blood, but acetate and celluloid. In Lee Oswald's mind, the scenes played again and again, the characters speaking directly to him, propelling him inexorably --Tony Fenner-like--to the martyrdom so gloriously promised in We Were Strangers.

_____________________________________

AN INTERVIEW WITH JOHN LOKEN

John Loken is the author of the book "Oswald's Trigger Films," which examines three films--We Were Strangers, The Manchurian Candidate, and Suddenly--and their connection to the assassination of President John Kennedy.

While it has been confirmed that Lee Oswald watched We Were Strangers, there is no substantiated evidence that Oswald ever viewed either The Manchurian Candidate or Suddenly. Yet it is these two latter films which are still the focus of attention from assassination buffs.

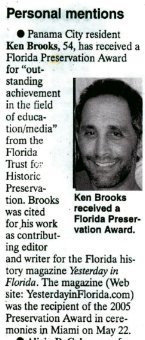

Ken Brooks recently spoke with John Loken about his research into We Were Strangers.

Q: You're convinced Oswald acted alone, emboldened by visions of We Were Strangers-style martrydom. Even if Oswald was a member of a conspiracy, wouldn't We Were Strangers still have provided inspiration?

John Loken: I would admit that We Were Strangers works as a motivator whether or not you believe in a conspiracy. But if you accept Oswald's "copy-cat" motive, you don't need the conspiracy allegations. In fact, you could argue that We Were Strangers takes the place of a co-conspirator. Rather than Oswald relying on cooperation from a real person or persons, you have this movie running over and over again in Oswald's mind. It's easy to imagine that he received a lot of emotional support from mentally replaying this movie.

Q: Did Oswald know President Kennedy was coming to Dallas when he saw We Were Strangers?

JL: The evidence suggests that he did. Oswald had just been to Mexico City, where he'd applied for a visa to Cuba and was refused. Oswald returned to Dallas on October 3, 1963, and that very week the newspapers announced that President Kennedy would be visiting Dallas in November. On October 12, Lee Oswald watched We Were Strangers. It was an amazing and tragic confluence of events.

Q: Why hasn't the We Were Strangers-connection received more attention from assassinationologists?

JL: Back in 1963, the concept of a "copycat crime" was virtually unknown. The term hadn't been coined and people were unaware of the phenomenon. It existed, sure, but hadn't yet been identified. That happened only in the 1970s and '80s as movies became more violent, and we learned more about the effects on young minds of graphic violence in the media. It's easy to forget, but Lee Oswald was only 23 when he saw We Were Strangers, barely out of his teens.

Q: Armchair psychologists are quick to point out the impact of early events in Oswald's life. Unstable home, truancy...

JL: That's my point: Aren't more immediate events just as likely to impact a person's life? The thing is: Oswald watched this movie twice. If he'd just seen it once--well, that could have been a chance viewing. But to watch the same film twice within 24 hours--how many of us do that? My favorite movie is Bridge On the River Kwai. But I'd never think of watching it twice in 24 hours. Oswald must have been enthralled, just captivated. Less than six weeks later, Oswald shot Kennedy. If this film provided just five or ten per cent of Oswald's motivation, its impact would still be momentous.

Q: And the movie has been virtually unseen since 1963, right?

JL: Personally, I'm convinced that Hollywood intentionally kept We Were Strangers from public view. I mean, John Huston was a major director and John Garfield was a huge star of the 1940s, which makes the film's disappearance for 40 years all the more inexplicable. Its disappearance is the main reason why the film has not been recognized in books about the assassination. No researchers could see it. If they had, it would have been impossible to ignore all the little details that would have connected so profoundly with Lee Oswald.

Q: The movie was never available in VHS?

JL: That's right. Columbia finally released in on DVD in 2000 but the marketing has been sanitized. The cover picture (showing Garfield and co-star Jennifer Jones in mid-embrace) makes it seem like a romance movie. Predictibly, Hollywood's response to the Oswald connection has been silence and denial. For example, Louis Menand, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author and a big movie fan and film reviewer, discussed my book Oswald's Trigger Films in a 2003 New Yorker article, in which he denied that Oswald was influenced by the assassination movies, writing, rather dubiously, that no self-respecting real assassin would have copied a movie assassin. Menand's logic is spurious, if you ask me.

Q: There are numerous examples of assassins-imitating-art. Wasn't John Hinkley, who shot Ronald Reagan, inspired by Taxi Driver?

JL: And Taxi Driver was itself inspired by Arthur Bremer's attempted assassination of presidential candidate George Wallace. They are links in a chain.

Q: Both director John Huston and star John Garfield were leftist Hollywood activists. In fact, during the 1950s Huston--like Oswald--chose to live abroad an as American ex-patriate. Is it likely that Oswald was aware of these facts?

JL: There's no evidence for it, but we can certainly speculate that he did. Oswald grew up in the 1950s. He was surprisingly well-read, a library-goer and a history buff. Surely he knew of Huston's Treasure of the Sierra Madre, which itself had anti-capitalist overtones. And we can assume Oswald knew about John Garfield, a major star who died in 1952, during Hollywood's red-baiting era. Oswald would have seen Garfield as a tragic, martyred figure--just as he saw himself. These are just more reasons for the film to have affected him so much.

Q: You made a trip to Dallas in 1998. Why?

JL: I had to wade through quite a number of volumes of the Warren Report in order to find out that Marina told investigators that Lee had watched We Were Strangers twice. But no one had ever substantiated that. In reviewing Dallas newspaper microfilm, I was able to confirm that KTVT did indeed show We Were Strangers twice the weekend of October 12-13. Over the years conspiracy theorists have traveled to far-flung locations attempting to uncover clandestine connections to Oswald. They've been to Minsk, Russia, to Chicago, New Orleans, Miami. And all the time the critical information was right under their noses, right there in Dallas. If only someone had bothered to check the newspaper movie listings!

Q: At the end of your book, you talk about Oswald's actions in the minutes after the assassination of President Kennedy.

JL: That's right: Where did Lee Oswald go after he committed his awful deeds? He sought solace in a movie theater--the Texas Theater, where he ultimately was arrested. Perhaps in his fear, his panic, his lonely isolation, he subconsciously returned to the one place where he'd always felt at home: the insulated world of the movies, where he was free to dream of martryrdom and violent glory.